The Indestructible Myth of the Sugar High

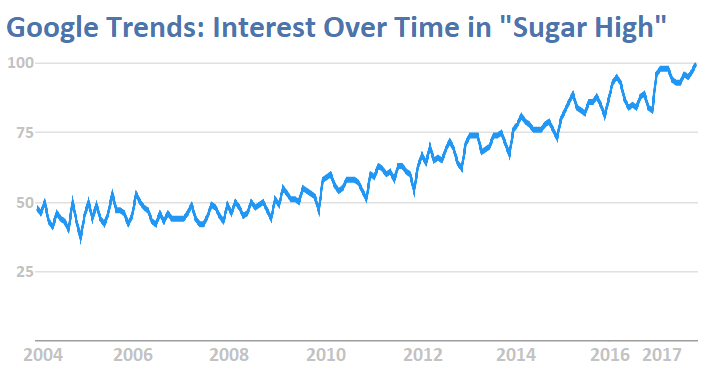

The Huffington Post asks if African Americans are “On a Sugar High?” That’s how they open a story about rising rates of diabetes. Health reporters offer advice for coming down from a sugar high. Tax cuts “Could Cause a Sugar High,” says Reuters.

The Huffington Post asks if African Americans are “On a Sugar High?” That’s how they open a story about rising rates of diabetes. Health reporters offer advice for coming down from a sugar high. Tax cuts “Could Cause a Sugar High,” says Reuters.

Oh, great! This buzz phrase connecting sugar, euphoria, and hyperactivity is so potent that economists are using it.

No, Sugar Won’t Make Your Kids Hyperactive

Many parents are convinced that Halloween and birthday parties will send their kids bouncing off the walls with too much sugar. But blinded studies consistently show that this just isn’t so. A 1995 meta-analysis in JAMA was pretty clear. “Sugar does not affect the behavior or cognitive performance of children. The strong belief of parents may be due to expectancy and common association.”

Of course, it’s possible that some individual children might be especially sensitive. And you’ll find plenty of parents who tell you their child is a special case.

Sugar and Dopamine

People who are making the case for food addiction compare sugar to drugs of abuse. They lean heavily on the release of dopamine stimulated by sugar and compare it to drugs like cocaine. A recent narrative review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine makes this case. The authors write:

Consuming sugar produces effects similar to that of cocaine, altering mood, possibly through its ability to induce reward and pleasure, leading to the seeking out of sugar,

What they leave out is that these effects are dramatically less with sugar than they are with cocaine. Emeritus professor Tom Sanders of Kings College London dismisses hyperbolic claims about sugar saying:

It is absurd to suggest that sugar is addictive like hard drugs.

While it is true that a liking for sweet things can be habit-forming, it is not addictive like opiates or cocaine. Individuals do not get withdrawal symptoms when they cut sugar intake.

In a 2014 review, Johannes Hebebrand and colleagues examine the evidence for food and eating addiction. They conclude that the evidence for calling sugar or any other food substance addictive is “poor.” They suggest instead that the issue might be addictive eating behaviors, not addictive food substances.

Finding Health and Pleasure in Food

Sweet treats might be pleasant. They might become an excessive habit. But they don’t make you high.

Let’s be clear. Too much of a good thing is a bad thing. An occasional sweet treat isn’t a health hazard. But a steady diet of too many treats leaves little room for more nourishing food. Calories pile up to create a metabolic train wreck of obesity. Pleasure slips out of reach.

This is not addiction. It’s just a diet that’s way out of balance.

Maple Sugar Season, painting by Horace Pippin / WikiArt

Subscribe by email to follow the accumulating evidence and observations that shape our view of health, obesity, and policy.

November 19, 2017

November 19, 2017 at 8:45 am, Susan Burke March said:

This sentence resonates! “… the issue might be addictive eating behaviors, not addictive food substances.”

A former client of mine could not deal with eating moderately, and instead is staying in ketosis, now convinced that “sugar is addictive” for him, and thus was uniquely responsible for keeping him from achieving weight loss. (grouped in there are all “carbs”).

November 19, 2017 at 9:58 am, Ted said:

Thanks for sharing this perspective, Susan!

November 20, 2017 at 4:10 am, John Dixon said:

Myths abound regarding sugar and obesity. Simple answers rarely solve complex problems. But this myth distracts us, and blames a single target, rather than allowing a focus on the very broad determinants of Obesity and finding a range of effective preventable measures that will work. It also distracts from effective therapy by providing a simple solution that does not work.

Let’s get real and address this epidemic seriously.

November 20, 2017 at 4:54 am, Ted said:

Powerful words, spot on. Thank you, John!

November 20, 2017 at 7:36 am, Joyce said:

This is a good argument (eating behaviors vs sugar addiction), but how would you explain the intense sweet cravings experienced by those who are recovering from alcohol or opiate addiction? What about reactive hypoglycemia? Is this also a myth?

November 20, 2017 at 7:56 am, Ted said:

All very good questions, Joyce. Food cravings are very complicated. We could fill a whole journal (like Appetite) on the subject of food cravings. Food cravings are very real, with a physiological basis, but they aren’t the same thing as drug addiction.

November 20, 2017 at 8:27 am, Elaine said:

Ok, if sugar is not addictive, explain to me why my blackberries, oranges, cooked broccoli and chicken etc. are still sitting in my refrigerator while any chocolates in my house call to me constantly until every last one is gone, in quick order. There is something in sugary foods that causes addictive behavior and pleasure and until research is done to explain it and eliminate it we will forever blame “addictive eating behaviors, not addictive food substances.” I guess we can blame our evolutionary past.

November 20, 2017 at 11:12 am, Martin Roy said:

Has your website ever taken the stance that sugar is bad in and of itself? This article, The Indestructible Myth of the Sugar High, seems to say that sugar is not necessarily the big evil that many are purporting. What is hard to understand is how so many seem to be addicted to sugar yet this article says it is not so. When does a ‘craving’ become an addiction or cross over into addiction? Does it at all? Each time some people define the new evil, others come out and say the statistics don’t bear it out. It used to be fat. Now it is carbs, or more specifically sugar. What will be the next big evil?

November 20, 2017 at 1:25 pm, Ted said:

All good questions Martin. Thank you.

At the end of the day, many things give us pleasure. We may find ourselves craving some of them. But that does not make them equivalent to an addictive drug like cocaine. When we get loose and fast with the science of addiction, our mistakes come back to bite us.