How a Person Gets Wired for Obesity

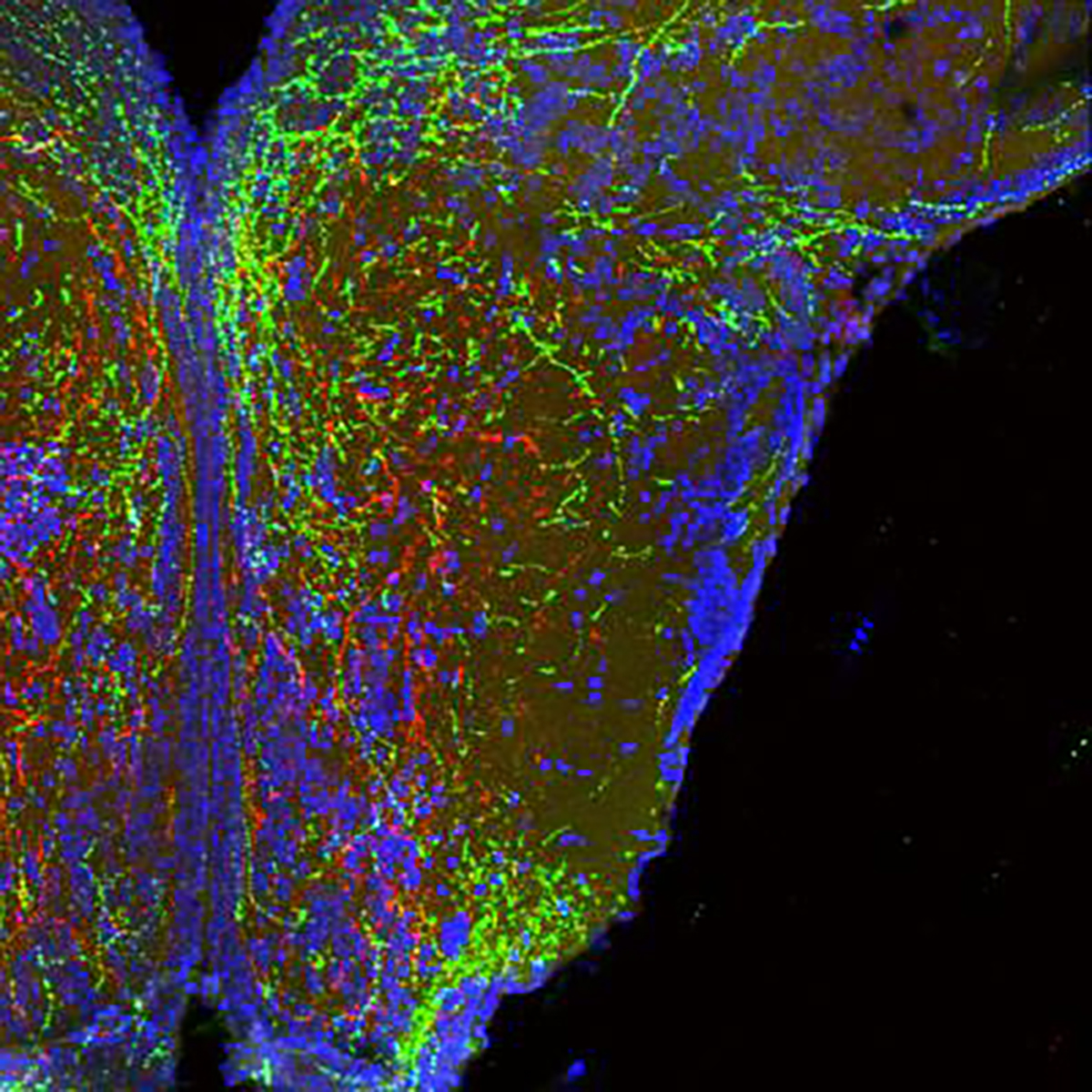

Long, wire-like projections of neurons in the hypothalamus that form body weight circuits appear red and green. Cell bodies from one area of the hypothalamus (bottom of image) branch up to another. Note that these cells specifically avoid some areas (appearing dark in the image) to seek proper targets. Image by Sebastien Bouret, CHLA.

New research published last week in Cell offers a glimpse of how a critical part of the brain gets wired for obesity very early in life. Sebastien Bouret, a senior author, explains:

We know that the brain, in particular an area called the hypothalamus, has a very important role in the regulation of food intake and blood sugar. What we don’t yet understand is how these circuits in the hypothalamus are being organized. We want to know how the brain puts itself together and what exactly governs that process.

The Developing Brain

Using animal models – zebrafish and mice – Bouret and colleagues studied how critical brain circuits develop in the very earliest stages of life. They showed that a protein called semaphorin 3 plays a critical role in guiding this process.

The pathways these scientists studied are melanocortin circuits. In the hypothalamus, POMC neurons interact with melanocortin-4 receptors to regulate energy balance. In part, this circuit determines how much energy an individual will consume, how much it will burn, and how much it will store as fat.

Semaphorin 3 provides something like a map for the developing brain. With this protein present, the melanocortin circuits develop normally to serve their role in regulating energy balance. But when the researchers disrupted semaphorin 3, those circuits did not develop correctly. The animals grew up to have excess fat.

Gene Mutations Show Similar Effects in Humans

In addition, genetic studies suggest that semaphorin 3 plays a similar role in humans. Sadaf Farooqi studies rare genetic mutations in people with severe obesity. She found 40 variations in semaphorin 3 signaling that seem to play a role. That is, without this protein working normally, people are much more likely to develop severe obesity early in life.

At this point, these findings are mere clues. It’s pretty clear that the hypothalamus plays a critical role in regulating our weight – just like it regulates our breathing and our body temperature. The process is complex. It’s critical for our survival. So these circuits are redundant – we have many backup systems in our brains.

Nonetheless, neuroscientists and molecular biologists are mapping out these pathways. Better understanding of how they should work give us a better understanding of how they’re failing when obesity develops. And that opens the door for better solutions than glib advice to move more and eat less.

Click here for the study and here for more about it from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Neuron in an Insect Brain, photograph © N. Gupta/ NIH / flickr

Subscribe by email to follow the accumulating evidence and observations that shape our view of health, obesity, and policy.

January 21, 2019

January 21, 2019 at 10:21 am, Allen Browne said:

Exciting. Another piece to the puzzle.

Allen