Childhood Obesity: Talking Crisis While Acting Casually

Crisis. It’s a time of intense difficulty. Or it’s a time when a difficult, important decision must be made. And finally, it can be a turning point toward either failure or recovery. For decades now, all the talk about childhood obesity has been about crisis. That crisis talk is spreading around the world as childhood obesity prevalence is growing globally. But while we’re talking crisis, how well do our actions line up with the talk?

A Crisis in Scientific Rigor

In a very credible way, Alexis Wood, Jonathan Wren, and David Allison tell us that we indeed have a crisis in the rigor of childhood obesity science. They recently explained this view in JAMA Pediatrics. As evidence for this crisis, Wood et al point to a string of retractions of childhood obesity studies.

In addition, they point out some of the special problems that childhood obesity presents. Methods are challenging, because studies must often use cluster randomization. Children often receive interventions in groups, not individually. In turn, this method reduces the power of a study and creates pitfalls for analysis. Other problems come into play, too, like regression to the mean and unreliable self-reporting.

Beyond the methods, childhood obesity brings strong feelings to the surface – stemming from blame, guilt, and stigma. Those emotions can get in the way of rational decision making. In addition, a sense of moral panic doesn’t help.

Wood et al tell us that no single answer will solve this problem. They recommend that transparency be uncompromising. But rigor in methods should adapt to the transparent goals of a study. We need to be more careful about drawing conclusions to avoid overreach. Statistical rigor could improve with greater involvement by statistics professionals. And finally they say, we need to elevate the importance of preventing, detecting, admitting, and correcting factual errors.

We Already Know What Works?

In sharp contrast, two weeks ago we heard calm reassurances. We already know what works to prevent childhood obesity. Dr. Ruth Peterson, who directs the CDC Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, repeated this assurance many times during a congressional briefing on the state of obesity.

In sharp contrast, two weeks ago we heard calm reassurances. We already know what works to prevent childhood obesity. Dr. Ruth Peterson, who directs the CDC Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, repeated this assurance many times during a congressional briefing on the state of obesity.

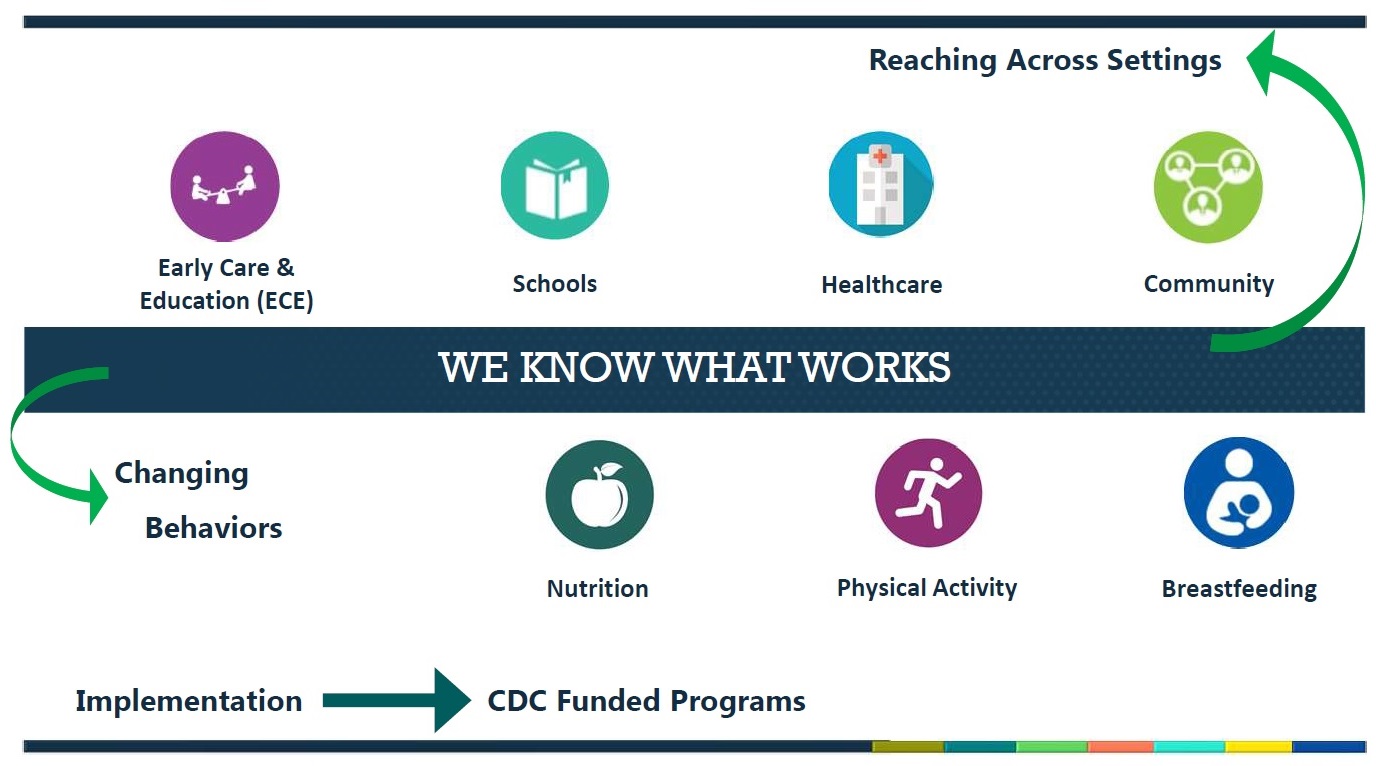

It’s a relatively simple formula: reaching across multiple settings with programs to change behaviors. The settings are early care and education, schools, healthcare, and communities. The programs are nutrition, physical activity, and breastfeeding.

Unfortunately, this reassurance doesn’t line up with continuing trends toward more childhood obesity – especially in more severe forms. Those trends led the Lancet Commission to conclude that “the current approach to obesity prevention is failing.”

Doing More for Kids with Obesity

Clearly, we haven’t quite figured everything out for preventing childhood obesity. Thus, we’re relieved to see pediatric experts developing a roadmap for better treatments. Right now, if behavioral programs fail a child with severe obesity, the only other options are a very few meds and bariatric surgery for adolescents. Writing in Obesity, Gitanjali Srivastava and a host of distinguished colleagues describe a pathway for more and better options.

Without a doubt, we have much work to do. We need better options for the kids who already have obesity. But most of all, we need more rigorous science to figure out how to reverse the trends. Talking crisis while acting casually is simply unacceptable.

Click here for the viewpoint from Wood et al and here for the report on the State of Obesity presented in Washington.

Confusion, photograph © Sylvain SZEWCZYK / flickr

Subscribe by email to follow the accumulating evidence and observations that shape our view of health, obesity, and policy.

March 12, 2019