Smarter Meal Timing for Better Metabolic Function?

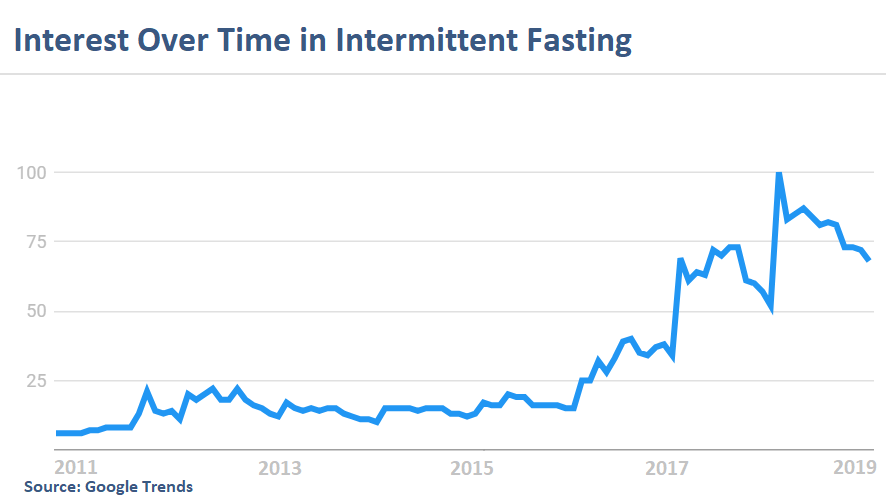

Sizzle and substance mingle in a pair of recent publications about meal timing and metabolic function. This is definitely a hot topic. People packed into the session on this subject at ObesityWeek. You can also see interest growing in Google search volume. But, as these two papers illustrate, we should read with caution.

Sizzle and substance mingle in a pair of recent publications about meal timing and metabolic function. This is definitely a hot topic. People packed into the session on this subject at ObesityWeek. You can also see interest growing in Google search volume. But, as these two papers illustrate, we should read with caution.

An RCT of Earlier Meal Timing

The first of the two papers we’ll consider is a well-controlled study of three versus six meals per day. The six meal regimen provided carbs and calories divided evenly throughout a 16-hour day. These subjects received breakfast, lunch, and dinner, plus three snacks. In the three-meal regimen, both calories and carbs were weighted toward the earlier part of the day. No snacks. In fact, the dinner meal delivered only ten percent of the day’s carbs and 13 percent of calories. In this regimen, the overnight fast was ten hours, while it was only eight for the six-meal group.

All of the subjects in this study had type 2 diabetes treated with insulin. Daniela Jakubowicz and colleagues published their findings in the December issue of Diabetes Care.

This difference in meal timing made a difference in metabolic function and weight. On the three-meal regimen, subjects lost an average of about 12 pounds. Though both groups received just as many calories and carbs, the six-meal group did not lose weight. In addition, these subjects had better control of their blood sugar on the three meal regimen. They required less insulin.

Because this study was well-controlled and randomized, it provides good evidence that meal timing makes a difference.

A Comparison to Baseline

In Cell Metabolism, we have a very different story on scientific rigor in studying this question. In that journal, Michael Wilkinson et al published a small, uncontrolled study yesterday. Based on their work, they claim that time-restricted eating “is a potentially powerful lifestyle intervention” for treating metabolic syndrome.

Beyond the obvious problem of a small study with no control group, Kevin Hall pointed out other problems with this publication:

Let me clarify the problem. While the paper reports the preregistered primary and secondary outcomes, it doesn’t identify them as such and doesn’t describe how the study was designed or powered to measure those particular outcomes. It isn’t obvious that the main results were null.

In other words, this study doesn’t prove much. All sizzle, little substance.

Promise and Caution

Good research tells us that meal timing and intermittent fasting have great promise for metabolic health. But when you have a hot topic, caution is wise. We get a diet of some solid, nourishing studies. We also get some junk science. Reader beware.

Click here for the study in Diabetes Care and here for the study in Cell Metabolism.

Clocks, photograph © Damien Walmsley / flickr

Subscribe by email to follow the accumulating evidence and observations that shape our view of health, obesity, and policy.

December 6, 2019