Sorting Out the Cost of a Broken Food System

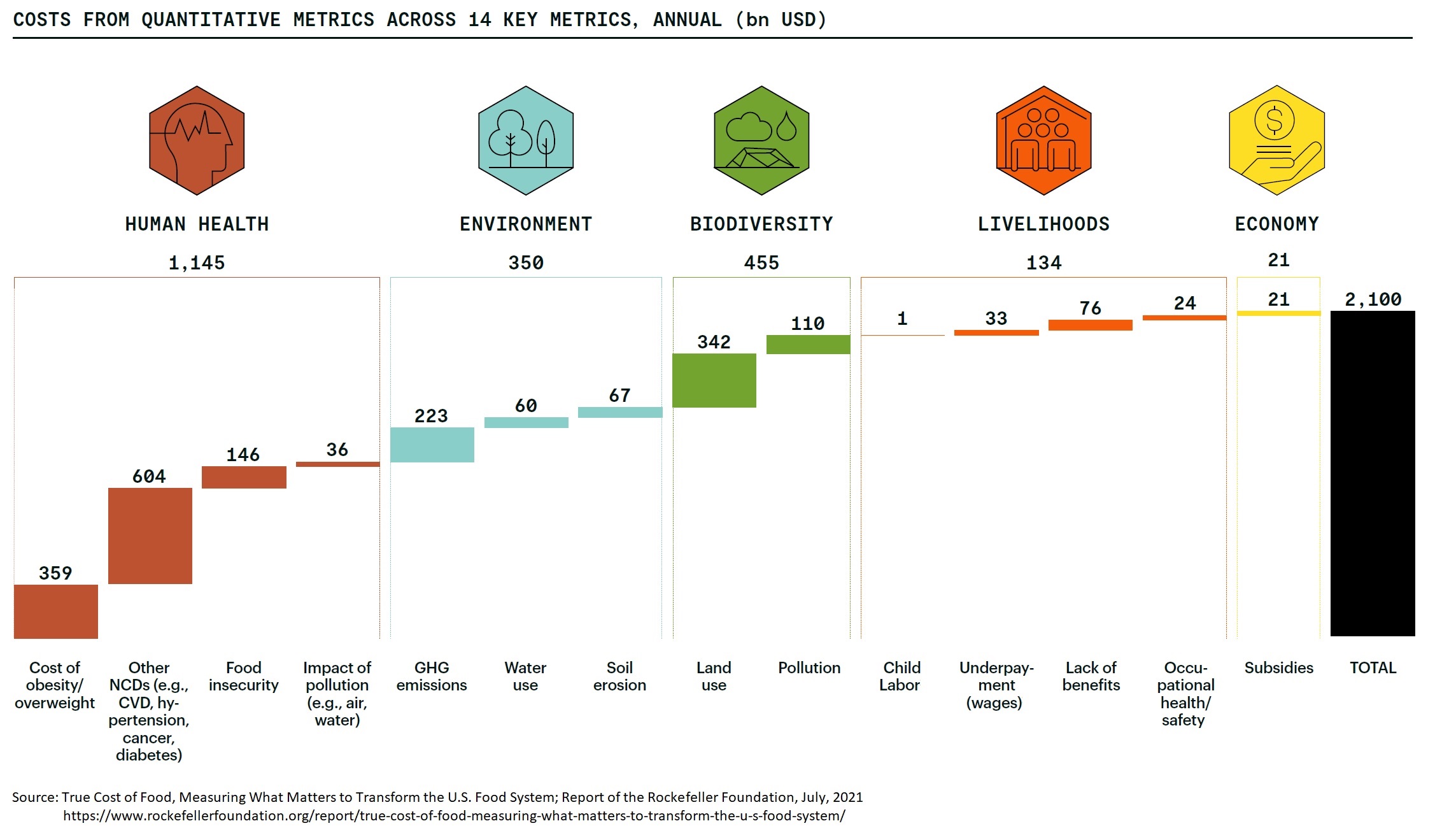

America has some of the cheapest food in the world. Out of pocket, we spend less for food than people in any other country in the world. Food beckons us to eat everywhere we turn. But the actual cost of cheap food can be quite high. A new report from the Rockefeller Foundation tells us that the true cost of a broken food system is likely three times higher than the cost of the food itself. In fact, cheap food costs our economy about two trillion dollars every year – because of lost health, harm to the environment and biodiversity, poor livelihoods, and economic subsidies. Those costs come on top of the trillion dollars we spend for the food itself every year.

America has some of the cheapest food in the world. Out of pocket, we spend less for food than people in any other country in the world. Food beckons us to eat everywhere we turn. But the actual cost of cheap food can be quite high. A new report from the Rockefeller Foundation tells us that the true cost of a broken food system is likely three times higher than the cost of the food itself. In fact, cheap food costs our economy about two trillion dollars every year – because of lost health, harm to the environment and biodiversity, poor livelihoods, and economic subsidies. Those costs come on top of the trillion dollars we spend for the food itself every year.

Rajiv Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, says this report is a call to attention:

“The U.S. food system as it stands is adversely affecting our environment, our health and our society. To fix a problem, we need to first understand its extent. The data in this report reveals not only the negative impacts of the American food system but also what steps we can take to make it more equitable, resilient and nourishing.”

A Successful and Failing System

Most public policy on food and agriculture comes straight from the 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health. The focus was on hunger and affordability. Obesity and the non-communicable diseases (NCDs) that result were not even a blip on the radar back then. Dariush Mozaffarian, Dean at the Tufts School of Nutrition, explains:

“The priority in the 1950s was to get calories into the world, because the world population had quadrupled. At the same time, the best nutrition information we had was about vitamins. Vitamin deficiencies have largely disappeared; we were successful. But we didn’t anticipate the explosion of obesity.”

Roy Steiner, Senior Vice President at Rockefeller, agrees:

“We created the food system with a particular objective — low-cost and abundant calories — and we didn’t understand what that impact was going to be.”

Costly Cheap Calories

Today, as the Rockefeller Foundation report describes, those cheap calories come from a now broken food system at quite a high cost. The rest of the world is following the path the U.S. has already traveled, as Phillip Baker and colleagues describe in Obesity Reviews:

“We find evidence for a substantial expansion in the types and quantities of UPFs [ultra-processed foods] sold worldwide, representing a transition towards a more processed global diet but with wide variations between regions and countries. As countries grow richer, higher volumes and a wider variety of UPFs are sold.

“The scale of dietary change underway, especially in highly populated middle-income countries, raises serious concern for global health.”

Everyone has a stake in fixing these systems, so we hear wildly conflicting stories about the changes that are urgent. Despite this cacophony, a few key themes are clear enough. First, agriculture must evolve to a more sustainable and more local model. Centralized and fragile supply chains did not serve us well in the pandemic.

Second, we should rely less on meat and more on plants. Animal agriculture can get better, but right now the impact on the environment and land use is unsustainable.

Finally, the food supply in our markets, stores, and pantries must do more to promote health and genuine enjoyment of food – and less to promote overconsumption of empty calories.

The challenge will be to translate these needs into a renewed food system that will meet them.

Click here for the report from the Rockefeller Foundation. For further perspective, click here, here, and here.

Taking in the Harvest, painting by Kazimir Malevich / WikiArt

Subscribe by email to follow the accumulating evidence and observations that shape our view of health, obesity, and policy.

July 24, 2021

July 25, 2021 at 9:19 am, John DiTraglia said:

So make food more expensive?

July 26, 2021 at 9:39 am, Ted said:

I think not, John. But it’s pretty clear that the food industry needs to get out of the business of prodding people to consume excessive quantities of empty calories.